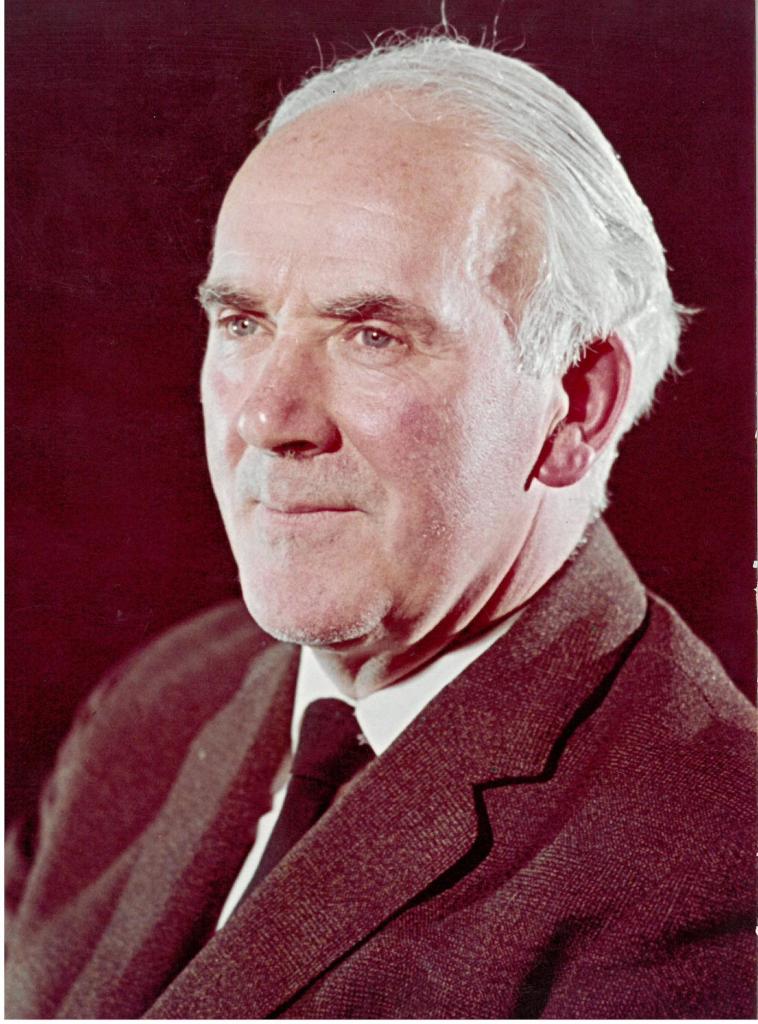

It is ten years since School Doctor, and later School Archivist, Dr. Robert Mackay, died. Bob was coming into School to volunteer his services in the archive into his 90s. Along with creating the first archive catalogue, Bob researched and wrote detailed histories of the School Doctors, which make for fascinating reading. In honour of Dr. Mackay, and the work he did for the School, we will be making some of his articles available online. This week, is a biography of the First School Doctor:

Foreword

I have for some time admired the work and writings of Dr. A. A. Mumford, the first medical officer of Manchester Grammar School. It seemed to me that he held views and practised medicine with children which was at least fifty years ahead of his time. He was, in every sense, a community paediatrician and although he started in medicine as a general practitioner, he became a consultant in children’s diseases as a result of the development of his own interests. His research work at the Grammar School and his teaching in lectures to earned bodies emphasised his belief that doctors should be working to promote the normal, healthy development of young people. When I discovered that apart from his own writings, there were only fragmentary records of his life in School, I felt inspired to research his life and write a short biographical paper about him.

I started this in 1998 and completed the study in 1999. By this time I had developed my interest in the project to feel that there was some virtue in continuing the writing to record the lives of the doctors who followed Dr. Mumford in the post as a contribution to the School archives. The information in School about these colleagues was just as sparse and amounted only to Ulula reports, though much more was discovered by research. I did not complete the paper about the fourth School doctor until early 2002. During 2001 there were hints and suggestions, with increasing frequency and insistence that I must write about the fifth doctor, myself, to complete the series. I felt, and still fell, unwilling to write an autobiography but because the information about the actual work done in School by the doctor has been so scanty since the days of Dr. Mumford, I now believe that there can be some usefulness in describing the work we have done in the last twenty years in developing the service to its present level. For the sake of completeness , I have included my curriculum vitae as a coda to this last section.

So many people, in School and elsewhere, have given me willing assistance in compiling these studies that it would be tedious to list them all here. All have been acknowledged at the end of each chapter except for the High Master, who graciously allowed me to appoint myself Honorary Medical Archivist on my retirement.

The Fifth Doctor

In January 1982 I received a letter from Dr. George Komrower, Old Mancunian and Governor, enclosing a copy of a letter to himself from the High Master, David Maland, writing after the sudden and tragic death of Dr. Arthur Berwitz. The High Master sought Dr. Komrower’s guidance in recruiting a Medical Officer for the School. As a personal friend and colleague of many years standing, George asked me for suggestions of some names of doctors who might be available and willing to serve. I did not know at the time that, apart from the practice adopted for the appointment of my predecessor, the School had always “headhunted” for a School doctor. I canvassed among my paediatric colleagues and eventually produced a list of five names including my own.

Why was I interested? I had retired from hospital paediatrics in 1980 and was working in Community Child Health part time. I had some spare time in the week for a new activity and though I had had many years of experience in “educational medicine” with children with severe disabilities and severe learning problems, I was interested in medical involvement with healthy adolescents.

I had a personal interest in being part of Manchester Grammar School. I had never attended as a pupil but I had known about the School from very early childhood. My father was an Old Mancunian (1904 – 1906) and I had admired his blazer with the First Eleven Cricket colours and the badge outlined in silver wire. His bat was enormous and I was told that I could use it only when I myself was in a first eleven. For reasons I never understood, I was taken to Long Millgate when I was very young to a building I found dark, cold and with lots of stone steps. We visited that gymnasium to meet Mr. J. Macaulay, the Head of Physical Instruction (1906 – 1945) having been an instructor since 1898. Two of my uncles were Old Mancunians and three of my cousins but I was never submitted for the Entrance Examination and MGS for the time being passed out of my life. So there were deep reasons why I added my name to the list and I have never regretted it.

As a result of this correspondence I was invited for interview with the High Master on May 11th and was appointed. Because of the pressing need for medical cover I was asked to start during the Summer term in 1982 and I attended for my first session on May 26th.

It is a matter of coincidence that all the doctors who have attended the School have taken their training in Manchester. I graduated in medicine in 1943 with Second Class Honours and prizes in Medicine and Surgery. I decided that I wanted to practice in paediatrics and took the necessary diplomas to qualify as a consultant. All this happened during the war the it is relevant that I was examined on several occasions by medical boards and pronounced unfit for military service. I therefore spent the war working in hospital departments not always in paediatrics.

So little has been recorded of the actual work of the doctor in the School since the chapter in Doctor Mumford’s book “Healthy Growth” (1927) that I have decided to give an account of the working of the team and how the programme has evolved.

The School Medical Service

I consider that, in a day school such as Manchester Grammar School, the functions of the school doctor as expressed in the work of the medical team are –

- To provide first line and emergency care for acute physical and psychological conditions affecting members of the School community

- To facilitate the adjustment to a full school life of pupils and staff burdened by ailments, disorders and disabilities having implications for life-style

- To foster a healthy environment and healthy, non-traumatic procedures in school life by advice to academic and managerial staff

- To invoke the co-operation of parents in furthering the adjustment of their son to a full school life.

- To provide a source of modern information and guidance on healthy life-styles

- To foster unimpeded growth and development of the young people in the School community

- To relieve the academic staff of the distraction and burden of the responsibility of attention to acute illness and injury in pupils

- To provide information and support to staff in supervision of extra curricular activities

The Medical Room

At some stage the ‘surgery’ was moved from the room occupied by Mrs. Furby in 1975 to a pair of rooms off the Theatre Corridor. These rooms had no natural light nor ventilation and were each about 10ft by 8ft in size. One of these rooms was used as a rest area, waiting room and overspill. The other was used for all other medical and general purposes. It was obviously cramped and unpleasant for the boys as well as ourselves.

After 1988 we began to campaign more vigorously for expanded accommodation and eventually space was released in a room at the eastern end of the main corridor opposite to the refectory. This had once been a science laboratory and was at the time the office of Dr. John Willson (Head of Science).

Although this room was an unusual shape, it was stripped and divided into a suite of rooms providing a waiting area, a therapy/consulting room, an office/privacy area, a rest and recovery area with three beds, a sanitary area with sluice and a stock room. This suite has direct skylight illumination and one opening window, heating and forced ventilation and appropriate plumbing. This improved accommodation transformed that quality of the service given and the working conditions of the medical team.

The development of extended premises made it possible to meet the increasing demands but it has been necessary to upgrade and modernise equipment to acceptable standards. An ambulance chair and a wheelchair with leg supports were purchased and the standard diagnostic equipment upgraded with an electronic sphygmomanometer and thermometer. A small refrigerator is used for storage of vaccines, cold compresses and other medicaments requiring refrigeration. The old fashioned steriliser has been replaced with a modern autoclave.

Since that time a private interview room (for counselling) has been provided a few yards away.

The availability of these facilities has les to a great increase in demand. The number of attendances per day varies greatly with the season, current epidemics and the distraction of examinations. Monthly averages reviewed regularly during my period of tenure and reported to the High Master, were about 40 per day with daily peaks from time to time of 50, 60 and a record 70 attendances in one day. In the last two years attendances have increased markedly with a daily average each month of approximately 60. The reasons for attendance varied from day to day, the most frequent being injury of some kind. These were mostly minor accidents and mishaps among the junior boys reflecting lack of co-ordination in a busy, unfamiliar environment and japes and fights. The senior boys mostly attended with sports injuries. In the last two years the balance of problems has altered with a great increase in attendances for consultation on personal problems and injuries are now a much less frequent cause of attendance. Sometimes there are more dramatic incidents but these are rare. Whereas the minor trauma can be dealt with in school, the more serious injuries are, after evaluation by the School Nurse, referred to hospital after parents have been informed.

Another large group present with minor acute intercurrent infections, mostly respiratory or alimentary, usually sporadic but sometimes in epidemic form. This pattern reflects the season of the year and holiday exposures. Again the policy is to provide simple symptomatic treatment to allow the boy to return quickly to class (no antibiotics are used) and in more severe illness a boy may have a period of rest and recovery or may be sent home in the care of a parents A wide variety of complaints not covered by these headings is seen every day and appropriate consultation and therapy is offered.

Psychological problems are a frequent cause of a boy seeking advice. None of these are ‘minor’ but many can be solved by a short discussions and reassurance but serious psychological illness does present perhaps with unacceptable behaviour reactions or with frank psychiatric symptoms. These boys require lengthy counselling interviews with appropriate consultation with parents, academic staff, general practitioners, psychologist and child psychiatrists. Frequently the School Nurse may spend many hours attending to these boys involving consultations in and out of school, home visits and case conferences with other professionals.

Medical Examinations

Because of the sudden death of Dr. Berwitz in December, the medical examinations of the first year entrants of 1981 had not been completed. We decided that the completion of those examinations was the first priority and in spite of any demands of the academic timetable, I worked on those until the end of term.

In the National School Medical Service, it had been a statutory requirement that pupils must be examined by the doctor five times, at specified intervals during school life. Dr. Mumford examined all boys each year and Dr. Brockbank had a medical interview with each boy every year and examined those in whom he felt that there was an indication. He did not always achieve 100% contacts and particularly regretted the shortcomings in the early days of the War. The usefulness of frequent examinations has diminished over the years with the improving health of young people. At the time of my appointment there were arrangements for two examinations – in the first and the fourth years.

My first administrative decision was to cancel the fourth examinations. In the first place, there was little justification for the interruption of studies in that age group for so little outcome and in the face of the backlog of work facing me, the examination of fourth years was an unrealistic project.

Over the years some details of the practice of first year examinations have changed but we evolved certain routines, the aim of the procedures being to ensure that every boy who was physically able to participate in all school activities could do so without reservation and that, in those instances of a boy having some limiting conditions, the academic staff were made aware of special circumstances requiring observation and care.

The routines were as follows:

Medical examinations were not started until the Michaelmas half-term to allow boys to become adjusted to the school routines and we hoped to be able to complete the series by the end of January.

In recent years, each form was visited by the School Nurse in the week before the examination was due to explain the system and reassure the boys – in particular that no needles would be used for any purpose whatever! In spite of this, scare stories persisted. During that week boys attended the Medical Room for vision tests and to present specimens of urine. (Special consent for that examination is now requested). We endeavoured to complete the examinations of a form within one week and during the sessions of that week boys were invited in twos and threes to attend the Medical Room. In this way, no boy missed a significant amount of a lesson and there was no crowding. The School Nurse marshalled the boys and was present in the suite during examinations. The examination itself was conducted with each boy in privacy, separated from his classmates with the Nurse observing.

The Medical Report submitted by the parents were discussed with each boy in turn to confirm that he knew his own medical history and immunisation status. The examination was very basic and was explained as it proceeded. It started with an accurate measurement of height and weight. Blood pressure was measured on each boy and those with asthma had an estimation of peak flow. Special procedures were used for boys with specific disorders but none of these were invasive.

At the completion of the examination the results were explained to each boy and appropriate comments made about health care and any need for re-examination . The interview ended with an invitation to questions.

The purposes of the interview were:

- To introduce boys to the Medical Room and service

- To determine that each boy was physically fit for the routines of School life

- To consider whether any condition reported or discovered might have an adverse effect in participation in school activities

- To draw the attention of boys with established disorders to their own responsibilities for health care

- To determine which boys by reason of established disorders needed particular awareness of the academic staff

The number of interviews and examinations each reflected the total intake into the first and later years. Usually every boy entering the first forms was examined. Later entrants, after explanation, were invited for examination but those over 16 years were given the option. This resulted in between 200 and 220 boys attending for examination in a season. About 15% of boys were known to have asthma and 15% were found to be significantly overweight. Unsuspected conditions of significance were revealed in between 3% and 7% of boys in different years.

For most boys the medical examination is a single learning experience. A small proportion of the group require more careful attention.

Boys with asthma were quizzed about their treatment and management to ensure that they understood the routines and that the Medical Room team was available in the event of problems. Boys significantly overweight were advised and re-invited subsequently for review.

The High Master was advised, with individual parental consent, of boys with significant disorders who might require special supervision and care in school life. Staff were invited and encouraged to ask for guidance on particular situations.

When findings emerged of important aspects of new or established conditions, I wrote to the parents with an explanation, an offer of consultation and advice to seek the opinion of the family doctor. In special situations I would write to the general practitioner but not as a routine.

Consultations

At each session I was available for consultation, in the first place with the School Nurse. When an opportunity presented we would discuss the problems of certain boys who had consulted her during the previous few days. These problems might have been physical or psychological origin but in cases of counselling the details remained confidential to the individual. The discussion might have been about management of physical problems and on occasion appointments would be made for boys to attend the Medical Room for full consultation. After explanation and the consent of the boy’s parents were also invited to attend for some consultations when circumstances indicated it but the Nurse had usually spoken to the parents beforehand suggesting that course of action and a report of my opinion was given afterwards either by phone or letter or both.

Members of the academic staff also attended for consultation about individual boys and sometimes with the parents for a general conference.

The only situation requiring a regular review was concerning boys who were judged to be significantly overweight on the initial examination. The judgment was made with reference to growth centiles and body mass index. I felt an obligation in the early 1980s to try to give these boys guidance on weight control and a healthy lifestyle in the hope of preserving their health in years to come. I had organised “weight clinics” in Salford in the 1960s and medical advice on this subject has become even more firm in recent times. Boys were invited every six months for review of their measurements and each time there was an explanation of the results with encouragement and advice as appropriate. This “clinic” was scheduled to detain boys for as short a time as possible and they were always given the option to attend in their free time if they felt any embarrassment. After each consultation a letter was sent to the parents quoting the measurements, their significance and the advice given to the boy. On the whole the letters were appreciated by the parents but there was an occasional protest and disagreement. On receipt of any objection, the sequence was cancelled. It was also necessary to discuss routine administrative matters and review policies and protocols.

Growth Survey

These consultations underlined for me a dissatisfaction with the growth centile charts available for children in the UK at that time. The original measurements for these charts had been made in 1959, though a Growth Study was in hand, no results had so far been published. I therefore sought the permission of the High Master, Mr. J.G. Parker, to conduct a measurement study in school. I managed to arrange to measure the height and weight of all boys in the school on two occasions in 1990 and 1991. From these studies we constructed, with the help of Alan Pickwick, the basis of a set of centile charts for the assessment of height and weight in clinical consultation. It so happened that the data from the Child Development Study was made available quite soon afterwards but our charts were still relevant to Grammar School boys. They enabled me to make comparisons with measurements made by Dr. Mumford and earlier observers in school. It is not surprising that the mean values for MGS boys were greater than the current national means and the means of measurements made over the past century. This work was done in the afternoons in my own time and was not charged to the School.

Health Education

Whereas Dr. Mumford and Dr. Brockbank gave regular lectures on health and medical topics, the modern curriculum in biological sciences and chemistry includes much that counts as health education and so my contribution was less expensive. I was invited to speak to junior and senior classes in biology on several occasions. i arranged exhibitions in the Display Area on genera health matters, on alcohol and on smoking. These were mounted for a few days at a time but involved an immense amount of work with the willing co-operation of the academic staff but the usefulness was very small and I did not pursue this programme. In recent years some medical experts have been invited to speak to senior boys, in particular a regular seminar on testicular cancer was arranged for seventh year leavers. Gradually, the tole of the health education in class was taken over by the School Nurse. who now addresses boys in form periods about First Aid and Health Promotion topics.

Immunisation Sessions

Routine and special sessions for immunisation were provided by the Mancunian Health Trust. The local administration and preparation was in the hands of the School Nurse with the help of the prefects but the Medical Room was the actual work-station. The routine administration of Diphtheria-Tetanus-Polio was done by the Trust team but I regularly took part in the BCG programme and in the special national programme on Meningitis C in 1999 – 2000.

We advised the school on prophylaxis for overseas trips through staff and boys were referred to their family practitioners or travel clinics for the injections or prescriptions.

Environmental Inspections

I made an inspection each year of the School environment and gave advice to the High Master and the Receiver/Bursar on matters affecting the health of the community. This started in early days when I was taken to observe and comments on an outbreak of vandalism in toilets. This made me realise that no-one had made an inspection for some years and that the Environmental Health Department was not involved. From that time, apart from special circumstances, I made an annual tour of the school including all departments, at first with the Clerk of Works of the time, Mr. Tom Hudson and latterly with the Caretake, Mr. Harry Bardsley. I was invited to inspect the Owl’s Nest on more than one occasion but not visit regularly. I made suggestions about dealing with the consequences of boys playing games in a field used for grazing and on one visit noticed a jar of peanut butter in the kitchen which I felt was an unnecessary hazard.

My reports included structural as well as management problems when I considered that they represented health risks to the community and were made in support of departmental managers. I was encouraged by the response of the school to my observations which led to an improvement in facilities, a reduction in vandalism and a modification of priorities to deal with health risks. Not everything was accomplished overnight, in particular the apparently simple procedure of opening classroom windows when occupied was most resistant to change. Mouse infestation was also resistant to attack not unrelated to the habit of disposing of unwanted food and wrappings in the desks and lockers in classrooms. This hazard was reduced by removing desks and lockers but an alternative risk was produced, in spite of clear edicts, in the development of piles of personal luggage in circulation areas.

A special inspection was called for after it was discovered that one of the waste disposal units in the kitchen had become deranged, discharging effluent into the basement instead of the drains. Fortunately, the doctor was not called for until after completion of the cleaning procedures which were meticulous.

I.T.

When I had been introduced to stores of old medical records in the cellars, in dusty confusion, I realised that a system of computerised medical records was the modern method of providing storage and retrieval. Medicine had not, at that time, clarified its ideas about the use of computers in medical practice and there was much talk about computers in diagnosis (perhaps the most difficult and questionable use) rather than tackling problems of records and communication. When I raised this matter in my reports, the High Master (then David Maland) was less than enthusiastic and I was discouraged. However, I sought out the colleagues on the academic staff who I thought might be more understanding. They were sympathetic and tried to be helpful but we made very slow progress. At first individual boys with computer skills were delegated to write suitable programmes but none were successful and the idea withered away. All the time the I.T. facilities in the School were advancing and the concept of computers in the medical service became more acceptable and natural. I continued with my efforts and persuaded Alan Pickwick to support me. After preliminary discussions he wrote the first useable programme for the Unix mainframe computer and I started to enter the data of medical records in 1993. The data were basic – identification detail a shorthand note of the medical examination and outcome and the immunisation record. Although we had attempted it, the record of daily attendances was beyond our resources. This was partly because the input depended entirely on my own efforts and time. As with the Growth Survey, this input was done after the routines had been dealt with and in my ow time, often after lunch. When the school system was changed to P.C. and Windows 95 the programme changed and we had to learn all over again but Alan rescued me for the second time by transferring all the Unix data onto the new system. Advice and training was also provided by Simon Duffy and the new I.T. department which included a patient consideration of commercial programmes on medical records. These proved to be unsuitable and far too expensive.

By the time I retired from the post of Medical Officer, we had seven years of complete records as designed which were constantly being retrieved by the medical room staff and individual records examined on request by pupils. The acme of achievement of my ambitions was when we were able, in September 2000, to provide each school leaver which a print-out of his personal immunisation history to take to his university medical service.

Administration

The Medical Room is a small unit and we are responsible for our own administration and budget control. Time must be found for discussion and decision on the medical system itself, the acquisition of equipment, stores and medicaments. Medical records must be prepared, completed and filed with respect for confidentiality. The procedures of consultation and therapy must be set up and modified in the light of experience. Protocols must be agreed and prepared in support of the working practices. Policies and management processed must be discussed with the academic and managerial colleagues and expenditure agreed. There is no set allocation of time for this work and much of the negotiation is done by the School Nurse.

After the half-term break each term I arranged an interview with the High Master to make an interim report on the work of the Medical Room, raising matters of administration and receiving his requests and suggestions. After the completion of the first year medical examinations, the High Master was furnished with a list of boys in the School who had ailments, disorders or disabilities requiring special supervision and care. The list was updated annually and the academic staff were invited to seek explanation and elaboration as they required. During the Summer Term, several weeks before the Summer Governors’ Meeting, I prepared a full report on the work done during the year. In this, significant illnesses and disorders were included. The report covered the outcome of the environmental inspection, a copy of which was presented to the Receiver (Bursar). The findings were discussed with the High Master at the Summer half-term meeting.

The School Nurse

In the area of medical work in schools, the nurse has had the primary role. Whether in the State schools as surveyor or adviser on health, as therapist in the school clinics, as ‘not nurse’ carrying out health inspections or as Matron in the boarding schools, the major portion of work was done by the nurse. School doctors had a supervisory role in times when it was regarded as necessary for the burse to have a medical person “in charge” to provide a statutory “cover”. Doctors had to provide for the regular statutory medical inspections and authorise the scheduled permitted treatments for minor disorders. In recent years nurses have been given greater responsibility and independence of action in attending to patients in many branches of medical practice and the role of the doctor in educational medicine has concentrated into some specialist fields though still providing a source of opinion for the nurse working in school. The work I have accomplished in School was only possible with the loyal co-operation of the School Nurses.

Mrs. Firby, the first to be appointed as School Nurse to Manchester Grammar School, took up duties in September 1975 and resigned in December 1979. Mrs. Anita McHugh followed her in January 1980 and was in post during the tenure of Dr. Berwitz for almost two years and unsupported after his death until my appointment in 1982. She held the post until her resignation in September 1988. After advertisement we appointed Mrs. Eileen Melody as School Nurse in the Michaelmas term of 1988. A second nurse (Mrs. K. Kitson) was recruited in 1993 as a part-time post to support Mrs.. Melody during busy periods and to cover study and sick leave. Mrs. Kitson resigned in 2000 and Mrs. F. MacNamara, a senior Practice Nurse with special qualifications in the management of asthma and of diabetes, was appointed in her place.

The prime duty of the School Nurse is to provide professional support for pupils and staff who develop acute illness, suffer injury or are overcome by psychological problems. Fourteen years ago, some 10-12 attendances per day was usual but this rapidly increased and now (2002) provision must be made for 60 attendances in a day. The majority of these are for acute illness or injury, most of them of minor degree (except to the afflicted). Psychological problems due to stress factors in school or situations at home may be reason for consultation but occasionally there are manifestations of underlying mental illness. It was been possible in recent years to make special provision for the 15% of boys who suffer from asthma.

Most of the problems can be dealt with by explanation and reassurance and the use of simple remedies for physical symptoms. More serious conditions may require referral after reporting to a parent for consent and support. Attendance on the individuals who seek help is not always a simple remedy speedily administered. The distress associated with an injury or the incoherent misery of a person stressed by a crisis may call for an extended interview, reference to staff or parents or a prolonger series of interviews considered as “counselling”. Both the duty nurses have specialist qualifications in counselling and recently a separate room has been provided, adjacent to the medical room, appropriate for prolonged interviews. Sometimes these situations require the contribution of other professionals, academic staff, specialist outside the school organisation and parents. The service has access to outside organisations, such as 42nd St., Gaddum Centre, the Brook Advisory Centre and eating disorders clinics for advice and support.

These provisions make it possible to give serious attention to instances of bullying, abuse, personal breakdown and mental illness. The presence of two nurses in school makes it possible to devote the enormous amount of time necessary to help the individual in distress without suspending the service to acute incidents.

A great deal of time is spent in consultation with parents, either by telephone or in personal consultation with or without appointment. A form tutor or other staff member may consult the nurse and/or doctor about an illness, disability or behaviour problem in a particular pupil, asking for advice on management and care. In such cases the rules of confidentiality are scrupulously observed.

The administration of a busy department also involves stock-taking and ordering of apparatus and medicaments. Much time and thought has been expended on improving documentation, referral letters, accident report forms, protocols and inventories to satisfy modern requirements of professional standards. Almost all medicinal treatment is with medication available to the public but medical authorisation of all medication on the inventory is underwritten by the School Medical Officer. The nurse also attends to the provision, equipment and replenishing of the 28 First Aid Boxes in the school departments and the kits taken to camps and on expeditions. The School Nurses are now involved in Open Days and Parents’ Evenings attending a stall displaying information about the medical service in school.

The School Nurse is, above all, an educator – in health matters. Every consultation and treatment includes explanation and instruction in the proper way to promote healing and avoid unnecessary complications. The Medical Room has several notice boards with posters and announcements of health topics and there is a rack of leaflets on relevant health matters of interest to boys. A major subject included in these displays is confidentiality – a subject very new to junior boys and one which needs emphasis from time to time.

The more formal Health Education involves didactic teaching in classes or groups and over recent years a systematic programme has developed involving the nurses in teaching in form periods on health promotion and First Aid. The nurses also provide a source of information for staff. In the first place, the doctor and nurses are part of the staff induction programme to explain the role of the medical department and the contribution it can make to the educational environment. The nurses are available to advise staff on general and particular problems in the care of pupils both in school and on extracurricular activities. Special advice may be given regarding certain sporting activities concerning the general safety of participants or the requirements of individual boys. Support for extra-curricular activities also involves detailed discussion with and advice to staff in charge of trips and camps on risk-assessment.

The nurses have taken part in the course planning and delivery of the P.S.E. curriculum. The School Nurse has been active in the development of the Independent School Nurse Forum of the Royal College of Nursing. By cultivating contacts between the nurses in schools in the North West, a vigorous group has grown of which the School Nurse is now the Chair. There are now regular, well-attended meetings with academic programmes for professional development.

Renumeration

I was interested to note an entry in the Minutes of the Governors Meetings of 1928 in which it was recorded that Dr. Mumford had offered to relinquish £300 of his emoluments of £700 to fund the employment of another doctor who would provide service to the Prep Schools. I wondered about the significance of such a reduction in income at the time and what it would mean in modern terms.

Dr. Mumford made a major change in his career in 1908. He sold his general practice, opened consulting rooms in Manchester and moved in to a larger house. This change is recorded in the autobiography of his wife, Mrs. E.E.R. Mumford, “Through rose coloured spectacles” in which she describes the period as one of financial pressures. The larger house was needed to accommodate their increasing family, then of five children (and servants) and the family finances were strained by the loss of income before the consulting practice gained momentum. Mrs. Mumford refers to the appointment to Manchester Grammar School as a significant financial contribution and describes the post as “full-time”.

Twenty years later the financial position must have been more secure to allow Dr. Mumford to make the generous gesture of providing the funds to employ a second doctor. There is no recorded information about Dr. Mumford’s remuneration until 1928 and it may not have been £700 from his appointment. if we apply a cost-of-living index to make a comparison with modern values, the £700 represents £19850 in 2000. [Using the National Archives currency converter gives a sum of £32000 in 2017 terms] A very important amount but not large in relation to the earnings of a consultant today, even in paediatrics. The cost-of-living index is not available for the years before 1918 but there was negative inflation after the Great War and the money might have been worth less in 1908. These comparisons are artificial in that financial priorities were different and Dr. Mumford did have some other appointments as consultant and advisor described in “The First Medical Officer”. Nevertheless, Mrs. Mumford began to write and publish books on nursery education, being invited to lecture to professional bodies and quoted as being an important authority on the subject.

It is not recorded whether the School accepted Dr. Mumford’s offer but Dr. Brockbank was offered, on his appointment, £250 per annum (£7088 in 2000) to provide services to the Prep. Schools o two half days a week. The money would have been a great help to a young doctor of 28, a bachelor, building a consultant career.

When Dr. Mumford retired in 1931, the remuneration was increased to £350 per annum for the responsibility of the whole school complex. Negative inflation still applied in those years and the income was equivalent to £11265 in 2000. Dr. Mumford had been twice that sum only three years earlier but the terms of the appointment had changed and was no longer regarded as “full-time” and probably involved four half days a week.

There is no record of changes in emouluments over the ten years but it is recorded that when Dr. Brockbank left for military service in 1941, he was receiving only £250 per annum (£5925 in 2000) but the Prep. Schools had closed at the beginning of the War and he spent two half days a week in School. There had been two years of significant inflation in 1939 and 1940.

Dr. Fisher accepted the locum post in 1941 at £175 per annum (£4150). It is probably that the financial stresses of wartime restricted the offer made to Dr. Fisher and more than likely that he understood and accepted the financial stringency out of public spirit and a modest and frugal lifestyle. Dr. Fisher took over the post of Medical Officer when Dr. Brockbank moved to academic duties in 1946. Dr. Brockbank had been paid £300 per annum since his return from the Forces (£7000) and Dr. Fisher was appointed with emoluments of £250 per annum (£5840). There is no record of his pay until his resignation due to ill health in 1975 when he was receiving £500 per annum (£2325). Such has been the effect of inflation since 1941.

When the Governors considered the development of a medical service in the school in 1975 according to the suggestions of Dr. Komrower, it was estimated that a full-time school nurse and a doctor attending on two half-days a week could be provided for £3000 per annum (£14000). No records remain of the remuneration of the nurse nor the doctor from 1975 to 1982, nor of the expenses of the service.

I do not recall an offer or negotiations when I began work at the School in 1982. The pay slips for the nine months of the first year, 1982 – 83, record payments amounting to a rate of £30 per session of 3.5 hours which, I presume, represents the scale applied to Dr. Berwitz. The total payment for that period of nine months was £1085 (£2150 in 2000). The rate per session was improved over the years, not always regularly, but the Receiver, Alan Martindale, spoke to me from time to time about increases in line with the improvements in the salaries of the academic staff. We made more than one attempt to discover from the B.M.A. and M.O.S.A. the current sessional rate for doctors attending day schools. We were unable to obtain a quotation from either organisation, being advised that negotiations on this matter were in progress without any completion date offered.

In the final year of the century the sessional rate had risen to £132.45. That was more than double the rate of inflation, which would account for an increase to £62.60 per session. Presumably that is explained by the improvement in salaries of the academic staff over the period. Although it was usual for me to attend the school twice a week, the actual attendance varied. When the medical examinations of entrants were in hand, I attended three times a week and in quiet periods such as the summer term, I would only attend once a week. The total number of sessions in the academic year of 39 weeks was usually about 70. The total payment for 1999-2000, my last full year of employment was £9627. This sum is equivalent to £340 per annum for 1928, the year of Dr. Brockbank’s appointment to attend the Prep. Schools of £300 in 1931 when he served the whole school complex.