This term is the fifteenth anniversary of the opening of the Junior Section at MGS. The School has a long tradition of educating boys younger than – in modern terms – secondary age (under eleven). The early MGS would likely have had a mix of age ranges. As the admissions registers for the early years are lost, we do not know exact details. However, prior to compulsory education, schools were flexible about the age that boys started. 1688 was the first year that younger boys were formally admitted to the School. High Master William Barrow set aside space in what was known as the “Lower” for boys to learn English for two to three years. Then pupils could move up to the main school to begin study in the Classics. In fact, they quite literally “moved up”, as the older boys were accommodated on the first floor of the school building above the younger boys.

Into the eighteenth century, the division between “Upper” and “Lower” schools began to blur, with age no longer the distinguishing marker. Our first admissions registers to survive from this period begin in 1730, and we can see that boys were admitted from as young as seven. Some boys never moved up to study Classics, leaving MGS in their early teens after receiving primary education in the “Lower” school. One famous example is that of Samuel Bamford. Jeremiah Smith’s printed admissions register devotes four pages to Bamford and states that “Young Bamford’s school days were early brought to a close, and he was sent when quite a boy to Manchester to learn weaving under his brother.” Bamford’s father had started out as a labourer before working his way up to become the manager of a Salford mill, and thought Bamford’s education in the “Lower” School sufficient.

By the time of Frederick William Walker in the mid-nineteenth century, the “Lower” school had begun to be phased out, with the School officially only educating boys of secondary age. The education acts of 1870 and 1880 meant it was a given that pupils arriving at MGS at age eleven had had some form of education in the basics of English. However, the School remained flexible on age of admission, with some pupils starting a year or two early if they were deemed able enough to manage academically. The original building containing the “upper” and “lower” floors was demolished in 1879. The curriculum was altered so that all boys would receive instruction in the Classics regardless of their age on admission. This continued until the late nineteenth century, when falling rolls led High Master John King to approach the governors for permission to open an MGS preparatory school, Such a school would act as a feeder for MGS and provide some stability for the future. King also wanted to see new boys better prepared for an MGS education. The first school to be opened was South Manchester School in Withington in 1896. North Manchester School in Higher Broughton followed in 1905. Boys were admitted to these schools from the age of seven. Simultaneously, a “prep form” was introduced at MGS itself for boys who needed extra tuition before they could enter the first forms. Many at the prep schools would make the move to MGS in the year they turned thirteen. However, some stayed on at their preparatory schools until the age of fourteen or fifteen. King tried to encourage such parents to move their boys on to MGS earlier by offering them a fee reduction. Whilst some would move to MGS, others, like Samuel Bamford decades before, would never join the main school and leave to enter employment. Sale High School was added to the roster of preparatory schools in 1908, when Cheshire County Council asked MGS if it would take it on. The three prep schools flourished in the interwar years, and many boys successfully made the move to MGS for their secondary education. The prep forms started by King persisted until 1924.

The Second World War led to the evacuation of two of the preparatory schools – North Manchester School to Kirkham and South Manchester School to Uttoxeter. Sale High School remained, being outside of the evacuation zone. The evacuations led to an exodus of pupils, with parents moving their sons to schools where they could remain day boys. Unlike MGS, the two schools did not request to return to Manchester, and by 1940 had haemorrhaged so many pupils that they were not deemed financially viable and closed. The fifty eight remaining boys were transferred to MGS and were accommodated in what had been the School Museum, becoming known as the “Preparatory” forms. The buildings of South Manchester School in Withington were taken over by Manchester High School for Girls from 1941 onwards, after their new buildings near MGS were destroyed in the Manchester blitz.

The School continued to admit boys aged nine and ten to the Preparatory forms throughout the war and the governors had initially planned to reopen both prep schools once the war was over. However, in 1946, the new High Master, Eric James, advocated not reopening North and South Manchester Schools, and to cease admissions to the “prep” forms. The School was undoubtedly overcrowded with over 1400 boys accommodated in a building designed for 1100. James wished to reduce admissions to a six form entry and to remove the Preparatory forms. The new direct grant scheme also complicated matters – could a direct grant funded school continue to educate boys below secondary age, whether as part of the main school or as separate fee-paying feeder schools?

He wrote:

“To ease the pressure on accommodation I would suggest that no further admissions be made into the Preparatory Forms at Manchester Grammar School. This will involve the elimination of the Preparatory Department though the process will take 2 or perhaps 3 years to complete.

At present there are 41 boys in the higher of these forms and 34 in the lower. A preparatory department in the main school has been clearly only a very temporary measure, and it is difficult to see any permanent justification for it, particularly as :

(1) The space is vitally necessary for the work of the main School

(2) The position of such preparatory departments has become unsatisfactory and ambiguous under the new Regulations [this referred to the Direct Grant scheme]

The arguments against the Governors restarting the South Manchester School are similar to those with regard to the North Manchester School: i.e.

(1) The difficulties inherent in having an independent preparatory school attached to a grant-aided Main School.

(2) The difficulties of maintaining satisfactory control over a number of satellite bodies.

(3) In the case of South Manchester, there is further the problem that the High School will certainly be anxious to retain the buildings for a number of years, and could certainly find no alternative home.“

The Governors went ahead with James’s recommendations, with the “prep” classes phased out and North and South Manchester schools closed permanently.

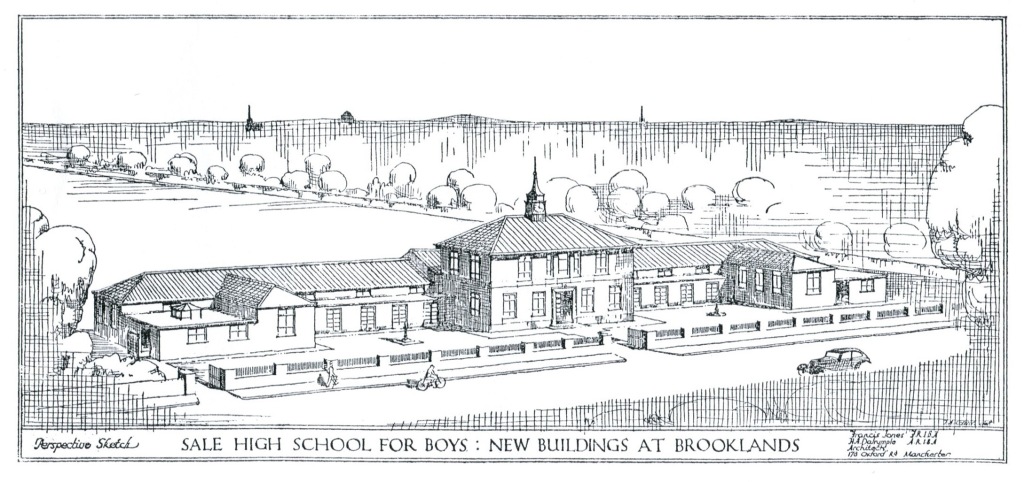

Sale High School clung on a bit longer. It had not had to contend with the problems of evacuation, falling admissions and financial issues that had dogged the other two Prep schools, but the tide was turning. James and the Governors felt it simpler to cut ties and focus on MGS and the opportunities to expand that the direct grant scheme offered. Because Sale High was still a going concern with boys and staff, the Governors arranged for the transfer of the School back to the oversight of the Cheshire Education Committee. The staff were retained and the School became Brooklands Primary School. This school is still in operation and on the same site and building as the original Sale High.

It wasn’t until the 2000s that the potential for the return of primary education at MGS was considered. High Master, Dr. Christopher Ray opened the Junior School in 2008, initially catering for boys aged ten and eleven (years 5 and 6). Then in 2011 the School was expanded to include boys of eight and nine (years 3 and 4). The Junior School, unlike the feeder Prep schools, is fully integrated into the life of the School, as well as being far larger, more developed and distinct than the Prep forms. The School currently educates 236 boys aged 7 – 11 in the Junior School, over 300 years since MGS first began to deliver a pre-secondary education for able boys. In addition, in 2013, the School helped to create New Islington Free School in Ancoats, with the School run by an independent charity set up by MGS. The then Deputy High Master, Stuart Leeming wrote “It remains the case that very many children cannot benefit from what we have to offer either because they cannot pass our entrance assessments, or because they are a girl, or because they cannot be funded. New Islington Free School allows us to extend our influence and ethos way beyond our traditional catchment and into a sphere that will allow children who would otherwise be very unlikely to benefit from an MGS education to enjoy much of what we offer to our boys.“